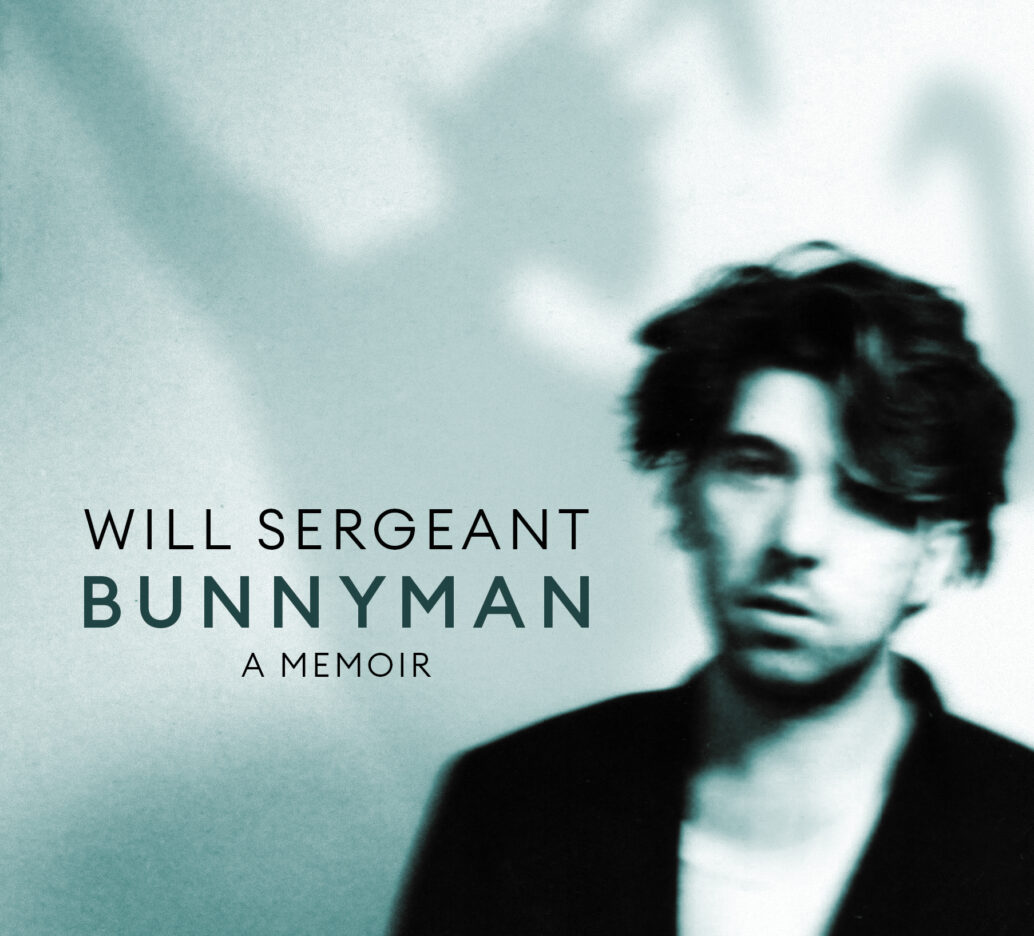

Within his recently released “Bunnyman” memoir, Will Sergeant, founder and the guitarist of Echo And The Bunnymen, looks back at the band’s formation and describes the history of his becoming. From the suburbs of Liverpool to the legendary Eric’s club, Sergeant goes along with the listener telling his story, which is inspiring and full of emotions.

Dan Volohov sits down with Will, who describes writing “Bunnyman”, the musical climate at Eric’s, realities of the ’70s and education system, “Ocean Rain”, and “Crocodiles”.

Over the years of your career, you’ve always distanced yourself from public attention. You even joked that when you do interviews, all the questions are getting answered by Ian McCulloch. So what pushed you to write a memoir?

WS: What happened was – our first four records got re-released on vinyl. And I was asked to make the liner notes, and I enjoyed doing it. I thought it was great and realised, “I can sort of do this!”. I was rubbish at school. So, it was a bit of a surprise that I could string words together that would make sense. I just enjoyed it and met some people who interviewed me, and they put me in touch with an agent.

He got me a deal, and that was it, really, so I started writing between 500 and 3,000 words a day. I did it nearly every day. If it was terrible weather like raining really bad – I didn’t write then (laughs) because it was a bit depressing and dark. Within the year, I’d done like 90,000 words, and none of it’s got taken out. Usually, big chunks get edited out or whatever, so It was all left in. I really enjoyed doing the book, and I’m going to do more. That’s the plan. So it’s just another thing. I like creating things, I like doing art, I like making music, and I like doing writing. It’s good.

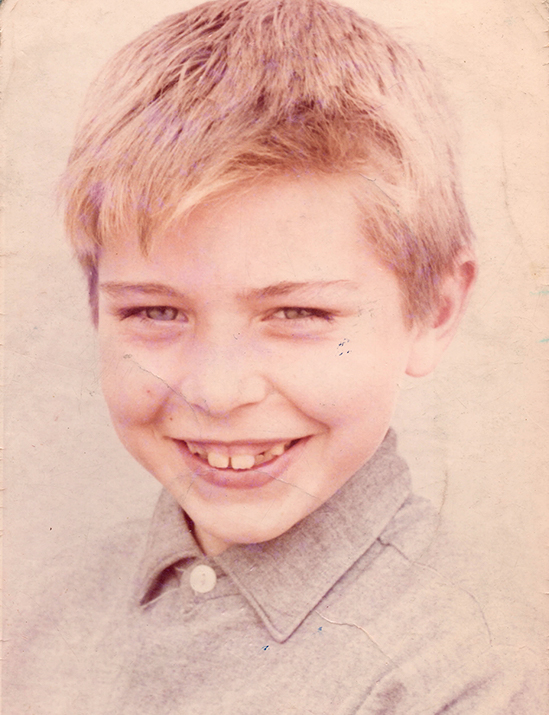

When you were writing about your childhood, did you feel the connection between William in your memory at 4-5 years old? Because a lot of people don’t. I think, when you just get older, you burn this bridge. And there’s no way to get back.

WS: Yeah, I know what you mean. It is challenging to put yourself back in that sort of five-year-old mind, but it’s still in there. And you just have to squirrel away and find it. I can remember it quite vividly being a kid, although certain things I don’t. I wish there had been more photographs. Nobody had a camera in those days. So, there weren’t that many photographs. Especially when punk-rock started, I’d love to see some more photos of what I looked like when I used to go to Eric’s when I was 19 or 20. There are no photos. There are few, but only really after the band started. I’d love to see one of those from the ’70s. But nobody had a camera.

The description of the atmosphere at Eric’s of that late 70’s era is pretty amazing. I remember Budgie telling me lots of stories from that time.

WS: Oh, Budgie, yeah-yeah. Budgie was there. He was in the band called The Spitfire Boys. And also, he was in Big In Japan, which was Jayne Casey, Bill Drummond, Holly Johnson, and Ian Broudie was in it. They all went on to do different things. Budgie was a nice fellow. I didn’t know him that well in Eric’s. I’ve met him after that, and he’s always been that nice.

Did you feel a sort of a family atmosphere there? Taking into account that at once, you found so many mutual thinkers.

WS: Because we were all sort of punk-rockers, it was all like a family, and you felt like you were in a gang, but in the actual club and in between different factions and different bands, there was a lot of jealousy and rivalry. It was awful. Like “They’re shit!” or whatever. It wouldn’t be like “Oh, I love your new record!” – it would be, “Oh…That’s shit!” (laughs). So it wasn’t all like happy families in particular. But in the whole movement of punk, there was a sort of solidarity between everybody. It just felt we could do anything. All of a sudden, it went from having to be some sort of virtuoso-guitarist or keyboard player to be in a band to be able to do anything you wanted as long as you got the spirit and the soul you’ll find your way through. That’s what Pistols and The Damned and all those other bands. That’s what they sort of brought to things. The Pistols could play, don’t get me wrong, their record is fantastic. Punk gave us the kind of confidence that it didn’t matter that we couldn’t play very well.

But when the labels started fighting for you – how did it feel? To get a contract in the ’70s, you should have been Jimi Page, and all of a sudden, labels were fighting for you.

WS: It felt very good. It felt like all we were doing was important. You get mentioned in the papers like New Musical Express or whatever. And in your mind, you think that the whole worlds’ attention is focused on a couple of little lines in New Musical Express, but it wasn’t like that. I thought we were the most important thing in music, art or anything. You have to have that sort of confidence to do it.

I was pretty shy. I was wearing punky clothes, but I wasn’t Pete Burns from Dead Or Alive or even Jayne Casey. She wore crazy stuff and would walk around Liverpool. I just liked a couple of little things like motorcycle boots or something and thought I was dead radical, but I wasn’t really.

In the fifth chapter of “Bunnyman”, you enumerate all the important events of that year. The Beatles were playing at the roof of the Apple building in Savile Row and mentioning Charles Manson and Woodstock. When I was reading this, I thought that everything that happened reflected both sides of music. On the one hand – you have two legendary acts of musical unity. On the other – one of the most terrible expressions of that dark part of rock music. How do you think what creates this duality, this conflict in rock music?

WS: I think any music reflects life, doesn’t it? So in life, there’s good and bad. It’s just the way it is. You can’t escape it. You have to reflect on what’s going on. So, there’s a duality, but it’s a valuable duality. It would be boring if everything were perfect all the time. You need some horror to make good bits seem even better. I do not suggest anyone do something like Charles Manson, but he wanted to be a musician. All the labels rejected him, and he ended up going a bit doolally. It was almost the same thing with Hitler when he got refused entry to some arts academy in Vienna or whatever. And he flipped his way and started channelling his anger the wrong way. I think it’s something similar that happened to Charles Manson. In a different time, he could be another Hitler.

There were quite a lot of songs that represent this duality in your music “Thorn of Crowns”, “My Kingdom”, of course, “Killing Moon”, “Angels And Devils”. They all are taken from “Ocean Rain”. What created this duality on the record, in your view?

WS: I think a lot of these songs – Mac wrote the lyrics to them. He’s always used this thing of opposites quite a lot like Heaven and Hell, inside out, outside down, angels and devils. He uses a lot of this sort of motif in his lyrics. So that’s just him. I think when you write a song, it’s great when you have light and shade all the time. And if everything’s on full blast all the way through, you have got nowhere to go. If you have dips and mood changes, you can bring the power back. Within the dynamics of the songs, opposite things help the dynamics and inspire the way of thinking about the lyrics.

Since the foundation of Echo And The Bunnymen, you’ve been attached to acoustic sounding – especially if we speak about “Pictures On My Wall”. Later you developed your guitar sound, up to the point where you got into more psychedelic or more avant-garde sounding. But what affected you the most back in those days?

WS: I don’t know; I was trying to be like somebody cool (laughs). I wasn’t trying to be a rock star or anyone like that. I was trying to be accepted in punk, in Eric’s. I never thought we’d get anywhere with any of this. I didn’t even wish we’d get anywhere. It wasn’t like: “Oh, great! We got to have a hit single…” – I wasn’t interested. It was about creating, to me.

I started with the 12-string acoustic, and it was just a strum fest. Strumming from chord to chord, I just got used to practising from chord to chord, and I got pretty good at it. The 12-string was because Bowie had a 12-string when he was Top of The Pops. So, he had a 12-string doing “Starman”. And I thought: “Oh, he’s going 12-string! I’m gonna do 12-string!” – even though, at that point, I could hardly play. Starting with a 12-string is a lot harder. You have to press down a lot harder because you have got two lots of resistance with the strings. And they are forever going out of tune (laughs). It’s tough to keep them in tune.

Nothing affected me back then. Just this feeling that you could do anything. Like punk had opened the doors. And I thought: “You could do anything! You can be anyone!” – all of a sudden, from being in a regular job and that sort of stuff, anything was possible. That’s what it did. I like computers and electronic music. If you got the ideas – it’s the ideas that matter. It’s not how you’re playing them; it’s having the ideas. And the rest of it sort of comes naturally. So, it’s the same sort of thing. Electronic music has opened up the doors so anybody can do it.

Is the process of creating the same for you? Does it still feel the same?

WS: Yeah, I don’t sit at home playing the guitar really at all. I’ve got too many guitars now. I don’t sit around playing the guitar just for fun. If I’m going to make some music, I’ll put the guitar on then. And every time you come to it, you come to it fresh because you’re not playing constantly, and new ideas appear. I want to create new ideas. I don’t want to repeat what I’ve already done or what anybody else has done. I don’t want to play other people’s songs. I don’t like playing “Stairway to Heaven” or anything like that. I’m not interested. What’s the point of trying to sound like Jimi Hendrix? We got Jimi Hendrix, or we did have Jimi Hendrix.

The book finished when Echo And The Bunnymen formed – when Pete De Frietas joined the band. What did Pete bring to the chemistry you already had and the songs that became “Crocodiles”?

WS: It made everything different. Because Pete wasn’t just the drummer, he was pretty good at arranging as well. He could play the piano, and he was more than just a drummer. He would contribute a lot. Some of the things we did maybe started with Pete, just doing a beat and then we’d jam along with it and then pick the good bits. But if Pete hadn’t begun playing that beat, some of the songs wouldn’t exist without him. A lot of the time, he was like the spark that created a fire. He needs a lot more credit than he gets.

The drum machine was great, but it was so primitive that we couldn’t have advanced. When Pete came, it just gave the whole thing twenty times more power. The power of his playing the drums was just ridiculous. He’d go on stage, and he’d come off being drenched from head to foot in sweat. I’ve never seen anyone sweat so much in my life from what he put into it. Pete had put 100% into it. He’d hit the snare drum so hard sometimes; he’d go and break the skin. We’d always have a spare snare, ready to swap straight away. Because sometimes he’d break the skins of drums because he struck them so hard. But he could also be very subtle; that’s another thing. It’s the same you were saying before about light and shade, Heaven and Hell. He could be thundering away on the toms and then bring the song right down. It made our songwriting capability a lot easier, a lot better, and more dynamic. When we had a drum-machine just ticking away all the time – It would go forever. It’s great, but it’s a bit one dimensional.

At the beginning of our conversation, you mentioned the continuation of your book. Will you go deeper into the Echo And The Bunnymen story or fiction?

WS: Well, I’ve always had the idea of doing fiction, but at the minute, I’m not just thinking about doing a second book – I am doing a second book. It’s going to carry on from where we first met Pete. Pete came down to Eric’s to see us, to meet us and to see us play our gig. And then, we went to rehearse the next day in Yorkies’ basement. We didn’t know anything about drummers. We hardly knew anything about guitars and bass – We didn’t know anything. So, when he played – we didn’t realise how good he was. We just thought: “Yeah! It sounds great!”. But as it developed and he added so much, we realised we managed to find the best drummer in the world ( laughs ). And he was going to go to Oxford University – Pete.

He was ready to go to Oxford, and he gave that up to be in the band. His parents were fuming – they weren’t happy ( laughs ) because he was only 18. He was 18, but he came from a much more privileged background than the rest of us. So, Pete knew a lot about stuff. He knew a lot and could speak French quite well. He knew about fancy food that we’d never seen or heard of, like croissants (laughs). It seems ridiculous now, but in the ’70s and ’80s, the food was terrible in England. It still got this reputation now, that the food is awful. It’s not awful anymore. He opened our eyes to a lot of things, a lot of cultural types of things.

As an artist, you’ve been trying many ways of artistic expression—songwriting and composing, painting and doing art performances. Now you have your book out. How much have these all affected your songwriting?

WS: I think, to me, it’s just creating. It could be anything; It could be painting or guitar or bands or electronic music or writing now. It’s just another form of creating. And I’ve just got that thing where I need to create stuff, you know. I don’t know why. I think, mainly it’s because I like and enjoy doing it. I like making something and think, “Wow! That looks cool!” I just like creative stuff. That side of my personality wasn’t brought out when I was in school because the school was rubbish (laughs). It wasn’t very good, and they didn’t understand kids. If you couldn’t remember dates of battles or stuff like that, you were deemed thick! A lot of people in our school weren’t stupid. They just weren’t sent down the right avenues.

Considering the number of creative forces of your generation, it kind of gets to a point where we can say that punk-rock gave you more than the education system did. Does it make sense?

WS: Once I left school is when I had my education. It’s the same for a lot of people. It’s not just me. Loads of people, when they leave school – that’s where they start to learn about life and things. They don’t teach you the right things in school ( laughs ). You come out of school – you have to know how to deal with taxes, all these sorts of things. But they don’t tell you about the useful things in life. When was the last time you needed to use algebra?

(laughs). A few months ago, probably.

WS: Yeah, but you don’t use it in your daily life. Unless you’re a scientist, which very few people are. Or microbiologists or something. They teach you the wrong stuff. They should teach you how to exist, and how to get through the days without getting depressed (laughs), how to navigate the dole system and what you need to do if you get a job. How to save up and put it in the right place and not waste your money. All these sorts of things. When you leave school – it’s when you learn. That’s your actual education, I think.

You said once that among your records from the ’80s, “Porcupine” was a different one – in particular, it was connected with “The Cutter”. What made it so different for you?

WS: It wasn’t that different; we had been playing live a lot and got good at playing. You develop a kind of six-sense sort of thing between all of us. So you know what the next person is going to do. I just think we got better and better, knowing each other and what we expected from each other. The great thing about The Bunnymen was everyone did their bits. So, it’s like four people’s ideas all coming together to make it. It wasn’t one person imposing all the ideas on the other people. And that’s what makes a great band. There’s like a formula sometimes to rock music, and it becomes very boring, very quick. But if you got four different people coming from four different angles – it’s never going to be that formula. I think “The Cutter” is a great track, but I don’t think it is much different from the rest we did. I think we improved all through playing live. Playing live, it’s like one of the best things you can do.

How does it feel when your childhood, your dramas and fears become available for everyone to read?

WS: My story is one story. It’s nothing unusual about it. It’s just I’m in an unusual position with people who might wanna read it. Lots of kids have a lot worse bringing up than I did. I was just telling what happened with me, my brothers and sisters, parents and friends. At that time, I wasn’t thinking: “Oh, God! We live through a horrible life!” – because we weren’t – It was just normal to us. You get used to it. You don’t know any difference cause you haven’t seen anything else. It’s only like later on when you become a parent yourself, and you look back and want to be loving to your kids and be kind to your kids. There wasn’t a lot of it going on (laughs). And it’s when you have kids yourself you think: that was probably a bit weird. We were like an inconvenience, you know. Not like joy, it was like not wanted. At that time, I wasn’t thinking: “Oh, poor me!” – I’m not feeling like this now. It’s just the way it was. Not a big deal!

Buy ‘Bunnyman: A Memoir’ by Will Sergeant here.

Be the first to comment