Mention Radiohead’s “Kid A”, to music aficionados and that one album title brings up significant discussion and disagreement. For every person who loves it dearly, there are those who dislike it and can rarely be won over to its merits. Is it one of the most brilliant albums recorded at the turn of the 21st century or a hyperbolized effort in esoterica? Whichever side of the fence you land on, the album was a watershed moment for the members of Radiohead. Where everything they had gained up until that point and everything they hoped to become was gambled on Thom Yorke’s desire to make trailblazing music that would keep them from becoming “fridge buzz”. Their audacious decision, that would off times become a seemingly endless tormented studio exercise, began their walk on a path less trodden and freed them from mere mortal expectations allowing them to become legendary.

Kid A was a major change of direction for Radiohead, as it compulsively looked to shake their fan base up and repel fair-weather fans that had been attracted to the mammoth popularity of OK Computer. On Kid A instead of continuing to utilize their firmly established guitar sound, they replaced it with synths, drum loops, brass and strings; while deciding at times to morph Yorke’s vocals until his voice was almost unrecognizable. The record would be an amalgam of Electronica, Krautrock, Jazz, and Classical genres with a heavy ladling of influences like Autechre, Aphex Twin, Charlie Mingus, Miles Davis, Bjork and Tom Waits. The project would conger up a plethora of descriptions but this fourth studio release could never be called either complacent or OK Computer Version 2.0.

Radiohead’s radical decision beggars follow up questions, why the departure when it would have been so very easy to create and produce OK Computer version 2.0 and grab a wedge of cash? Why bring the band to the point of implosion? Why enter a constant battle with their record company to justify the project, when label representatives call Kid A career suicide? The decision seemed tantamount to a self-harming exercise. Especially considering the fact that the band had at least 5-7 songs from the OK Computer era they could have whipped together, released and heard no complaints from the marketing department. There are no simple answers other than each of the band members’ integrity and gut instinct told them a new sonic path would be the better one to take in the long run.

When considering the band’s next move each member needed a new motivation. This was especially true for frontman Thom Yorke who needed a justification to continue in the music industry. He had reached the pinnacle of fame and found it impossible to live within its madness, there had to be something more. After the final show of the OK Computer tour, the members of the band were burnt out. Each band member to some degree has been troubled by what should have been their shining moment. Yorke would suffer a nervous breakdown; Ed O’Brien would struggle with lesser-known emotional problems. Phil Selway worried the band was being destroyed by success, Colin and Jonny Greenwood realized things had to change or no one would be able to tell Radiohead apart from the growing number of imitators. Added to Yorke’s mental health challenges post OK Computer, he also had a serious case of writer’s block and was unable to finish songs he was writing on guitar. He began to almost exclusively listen to electronic music. He found solace and a toehold back to songwriting in electronica’s lack of human voices and how the music was still able to convey emotions. The seeds for what would eventually become not only Kid A but Amnesiac would incubate during this period.

There was a much needed holiday for the band in late 1998, during which time Yorke would sit at home by the sea in Cornwall only playing the piano. Ed O Brien would gain peace of mind travelling in Brazil. The band reconvened in 1999 to work on the new release. Ed had hoped to create snappy melodic tracks; however Yorke ever the benevolent band dictator was having none of it as he had, had his Damascus moment. He would state “there was no chance of an album sounding like what O Brien wanted. I’d completely had it with melody, I wanted rhythm. All melodies to me were a pure embarrassment.” Needless to say, along with concern about how little advance work there was to use as a template for Yorke’s vision, there was also a lot of consternation from the other band members as to Yorke’s goals and the possible fallout.

With serious doubts taking root the band would meet in Paris under no label enforced deadlines and with producer Nigel Godrich again working the sound desk. Yorke was still suffering from writer’s block and everyone was struggling in the dark to get a grip on what was expected. At one point in the sessions, Jonny expressed concern that things were getting entirely too esoteric and the result would be god awful art-rock nonsense. Colin would back Jonny’s sentiment feeling there was a great chance that the band would cut their nose off to spite their faces if they got too precious. At the lowest point, even Godrich pondered the wisdom of the band abandoning their strongest asset, their ingenious guitar sound. Each individual involved would eventually buy into and come to trust that Yorke’s vision would work out and was worth pursuing.

By the end of the Paris sessions, the band had worked through most of their insecurity with the new direction. So much of that insecurity stemming from the leap of faith each needed to take as suddenly not every band member was necessary to play on every song. This leap would test the relationships of the bandmates who had been friends since school. Ed Obrien would describe it best, “It’s scary, everyone feels insecure, I’m a guitarist and suddenly it’s like, well there are no guitars on this track or no drums.” The changeup in their typical recording approach sent band members to other musical instruments and sonic techniques; such as the Ondes Martenot, modular synths, computer software and began O’Brien’s initial love affair with sustain units, looping and delays. There would still be a long way to go in the studio. The band in March of 1999 would move to Copenhagen and only produce 15 minutes of music after 50 hours of recording with nothing finished. The band would return to England and after some time in a rented Gloucester Mansion return to their newly renovated studio, Canned Applause. Sadly the only thing accomplished in Gloucester was the band agreeing that they would break up if they could not agree on the release worthiness of the album.

At Canned Applause, the band would continue to struggle but by the end of 1999, they had completed 6 songs including the title track. Early 2000 would see Jonny Greenwood suggest bringing in an orchestra. The St. John’s Orchestra would struggle at first with Jonny’s suggested compositions but eventually would open up to his experimental orchestral constructs. The breakthrough would occur with the recording of Everything In Its Right Place. With the completion of that track, the toehold the band was so desperately seeking finally occurred. The picture of what the album could begin to emerge. From that point eventually, 20 songs would be recorded in the Kid A/Amnesiac sessions. As the prolific nature of those studio, sessions was being revealed the record company suggested a double album, but the band could not agree on a playlist and Yorke feared a large format would ruin the impact of the songs. Instead many of the tracks not utilized for Kid A would appear on Amnesiac which as Yorke would later state became an explanation or another take on Kid A.

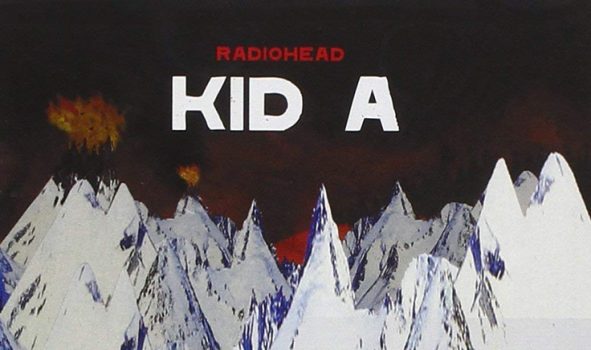

Kid A would be released in October of 2000. Counter-intuitive to the music label marketing of the time there would be no singles, no music videos and very few interviews. Instead, the band would utilize the internet making the album available for streaming and using short animated films featuring artwork to promote the album. They would take themselves out of the marketing strategy and push for the content of the album to speak for itself. The results are indisputable. Kid A debuted at #1 on the UK charts and went platinum in its first week. It was also the first #1 album for Radiohead in the US. It would win a Grammy for Best Alternative Album and be nominated for Album of the Year. By 2010 it would appear in numerous greatest album lists. With Kid A Radiohead had gone out on a tree limb with a saw in hand and instead of hacking off their successful career built a gorgeous treehouse that everyone ever since would love to replicate.

The album starts with Everything In Its Right Place the watershed track starts the release off as a cohesive work. The title of the song spoke to obsession and perfectionism, the need for everything to be exactly just so. It was critical of the wrongheaded idea that there is only one way things can be, only black and white, described in the lyric, “There are two colours in my head.” The feeling is closed off and isolated with an internal dialogue that is in many ways a word salad. The repeating refrain builds the impact and universality of the lyrics. Of note, as always Yorke, when he is singing his most sweetly is when he is at his most insightfully acidic. The same thing takes place on Kid A with the obscuring of his vocals adding emphasis.

The title track, Kid A acquired its name from one of Radiohead’s studio sequencers. Like a disturbing fairy tale diorama, the song displays the road to hell is paved with ulterior motives. Images abound including the Pied Piper, puppets, plebeian revenge and the nightmare figure that stands at the end of the bed and resides in the subconscious. This is all played out with the story of the Pied Piper leading the children and rats out of town and the sinister last phrase, “poor kids”. The otherworldly sonics of Yorke’s dissociative vocal, the drum tattoo and the ethereal sound effects create this paradox of innocence and violent/sinister feeling. This is the song that hooked me when I first heard the recording.

The National Anthem is a song that separates the sheep from the goats and is the most challenging selection on the release. You either love it; I raise my hand, or can never be convinced it is a masterwork. There are very few lyrics to the song, but those that are there transmit completely the feeling of being lost in the crowd. A crowd that is rushing headlong into god knows what with extreme fervour; kind of like Nationalism. Yorke suggests the idea that being unique and not conforming is the unspeakable fear of those in authority. Sonically there is this cacophony like a traffic jam that was inspired by the organized chaos of Town Hall Concert by Charles Mingus. It was only when I got into Mingus and Miles Davis that I came to fully appreciate this song in all its majesty and cathartic impact. I am still blown away by the audacious and fearless manner in which this song was presented. The buzzsaw opening with throbbing bass and that wall of sound frontal attack is something to savour as it serves up confusion and stimulus overload. Yorke’s disembodied voice is like a cry in the emotional wilderness as that fat horn and cymbal bang away. The crescendo of out of control horns that swoop and dive like a kite on the wind bring the song home on one of the most breathtaking songs of the 2000s.

How to Disappear Completely is a song that is a bridge from the OK Computer era, and almost creates a quandary as to how it ended up on the release. How to Disappear Completely sticks out from the rest of the album as instantly recognizable from an early manifestation in the Radiohead documentary Meeting People Is Easy. I have come to square its existence on the release as the lyrical explanation for psychical pain Yorke went through during the OK Computer era. Hence the track fits with the overall sentiment of the album. The song contains that forlorn mantra to help get through a decidedly painful confrontation with fame. It paraphrases advice given to Yorke by REM frontman Michael Stipe, “I’m not here, this isn’t happening’. Since the release, that chorus has helped many individuals to pull through monstrous events and the sentiment remains evocative and heartbreaking. The song is also in contrast to the first three tracks which are loaded with impersonal isolation and disaffection, How to Disappear Completely provides the first real glimpse into Yorke’s injured psyche and how much the demands of fame cost his well being. The acoustic guitar and Ondes Martenot provide an instrumental setting of pathos for Yorke’s emotional dénouement to unspool over. I have always thought the cacophony at the end of the track represented the emotional breakdown Yorke encountered after the tour. The end of the song becomes a kind of roman a clef with the reference to strobe lights and blown speakers acknowledging the stress he was under when the band conquered Glastonbury in 1997 with their headliner gig. How to Disappear Completely is still one of Yorke’s all-time favourite Radiohead songs. Out of all the gorgeous songs created by Radiohead, this one hovers at the top.

Treefingers is an instrumental and the amuse-bouche of the album. It serves as a palette cleanser that prepared the listener for the second half of the album. The otherworldly processed piece floats along like some kind of interlude where the listener floats majestically in the interstellar universe.

Optimistic is not usually a word that springs to mind when thinking of Radiohead’s works. The song is the antithesis of positivity with its disturbing images of carrion with vultures circling and the dog eats dog rat race of our existence. The initial pessimism is broken by the refrain “If you try the best you can, the best you can is good enough.” Two themes are juxtaposed, the gut-wrenching with the reassuring and results in a push-me/ pull me situation. The track also takes humans to task for not acknowledging our future is unsure. There is folly in of our optimism and the belief that extinction will never happen to us. Optimistic is the most straightforward rock song on the release. It takes advantage of an extraordinary rhythm section and gritty guitars to produce an almost tribal atavistic vibe. The cool groove ending is something to be enjoyed as the song segues into In Limbo.

The psychedelic sounds of In Limbo are alluring with the spiralling guitars that convey a muddled lost feeling. I have often wondered if the inspiration for the track was Yorke’s time spent on the Cornwall coast attempting to recover his equilibrium. The song was possibly his attempt to come to grips with how it had all gone so pear-shaped “I’ve lost my way” and his dealing with all the anger he felt at being misled by the chimaera of fame. The track has a lot of awkward angles but works well as a kind of fugue hallucinogenic offering.

Idioteque is pure genius with its extraordinary mixture of Dance, Kraut Rock, Electronica and slab of paranoia. There is a certain kind of madness that is captured in the catchphrases and word salad that are the lyrics. There are a number of topics discussed, the pitfalls of rock stardom, arrested development, climate change and robotic takeovers. Included is the declaration that fame is certainly not all it is cracked up to be, “Here I am allowed, everything all the time.” This is all put to a drum loop you cannot escape and punchy thump punctuated by glitchy electronics and Yorke’s pitch-perfect delivery. Live this song is a barnburner and you cannot help but dance. The spirit moved on this one creating a giant of a song and a timeless classic.

The track Morning Bell would turn out to be such a great song it would not only be released on Kid A but another version would appear on Amnesiac. This song has always felt to me like the little brother to No Surprises as it examines all the frustration and ennui of suburban life. Depicted is a romance that turns sour; all that is left is the distribution of the material goods. The track’s lyrics off-handedly split the children in half so it is all fair and respectable with no thought to the consequences for the kids, excoriated ultimately is that utterly coldblooded thinking. The refrain “release me” pleads for a release from the matrix of conformity and middle-class respectability that is both terrify and moving in equal parts. It is here that Yorke’s insight delivers a blow upon the bruise that is our damaged culture. The sonics build the drama that starts with a feeling of everyday innocence and explodes with Jonny’s incendiary guitar like some kind of momentary loss of composure and then the calming afterglow.

The sign off to the album is Motion Picture Soundtrack a disturbing lullaby telling a nightmarish tale about fame driving one to the edge of sanity. The bleating organ and Yorke’s heartbreaking forlorn delivery provide a song that is almost overloaded with loneliness. Harps lift the mood just a smidgen from the lacerating self-examination of the narrator’s white-knuckled attempt at surviving a torturous experience. The track is unsettling as concern is raised about the almost suicidal farewell of the sign off “I will see you in the next life”. The hidden sonic at the 2:42 mark may provide the final sentiments as a single celestial note explodes into an interstellar burst possibly echoing that last line and the arrival at reincarnation or a final heavenly destination. The song reverberates as Radiohead’s evocative take on the finale of life until the remarkable Videotape off In Rainbows.

In so many ways Kid A is an intriguing walk through the minds of 5 brilliant individuals viewing their misgivings, fears and demons. The album that at its release some critics and music industry professionals called a commercial suicide note has gone on to become one of the most esteemed albums of the 2000s. In fearlessly refusing to give in to the easy impulse of selling a lot of records producing music they could create in their sleep. Radiohead instead challenged themselves and released a stunningly brilliant album for the ages. Counterintuitively they gained additional adherents to their already rabid following and freed themselves from the whims and crotchets of the music industry’s demands. Kid A, in the end, is a kind of auditory Jackson Pollack painting that can seem pointless at first but when listened to carefully reveals unfathomable meaning and beauty. Those attributes keep listeners coming back for more as Kid A addresses numerous moods with its rich and dense layers making it timeless in the universality of its impact and a masterpiece.

Be the first to comment