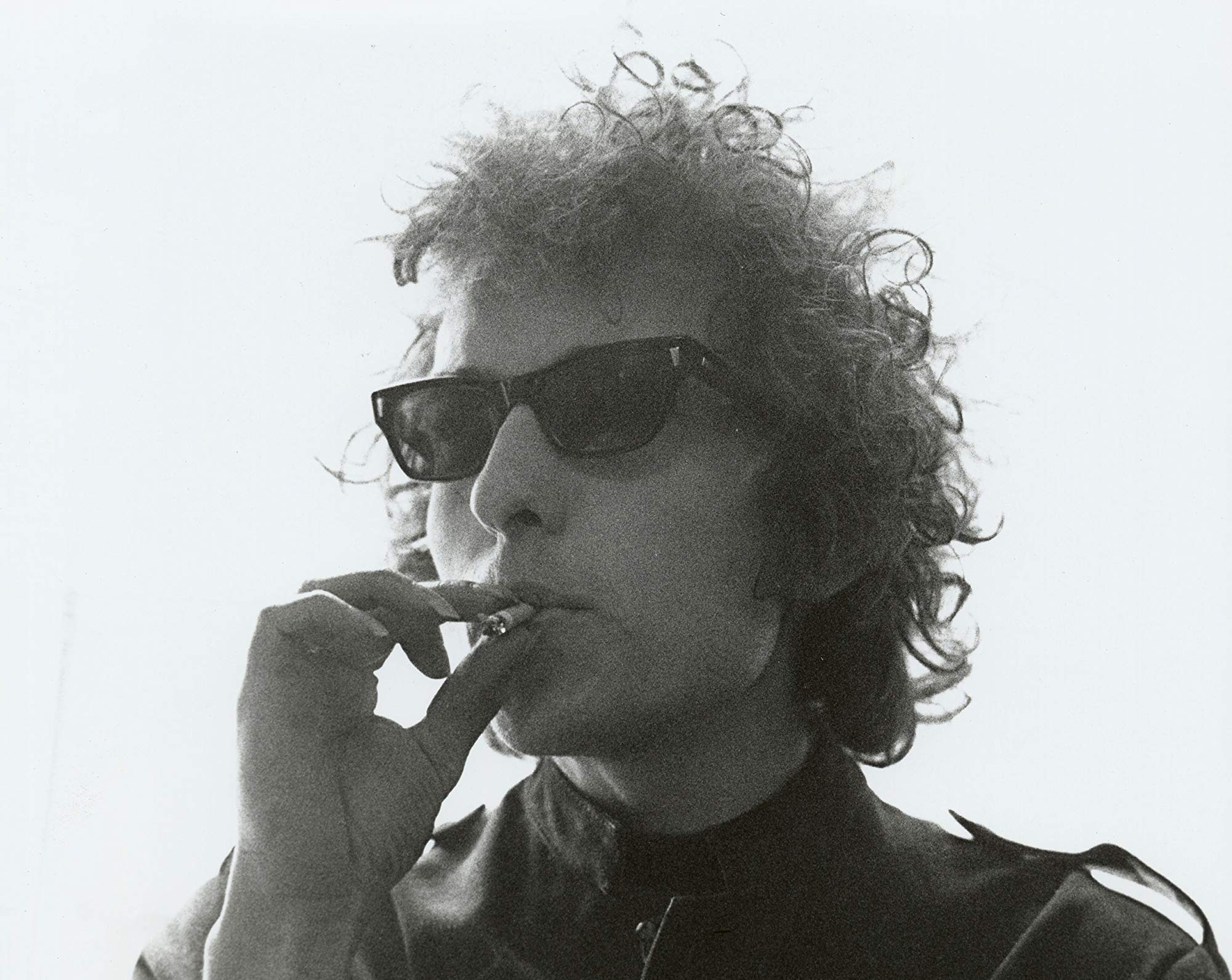

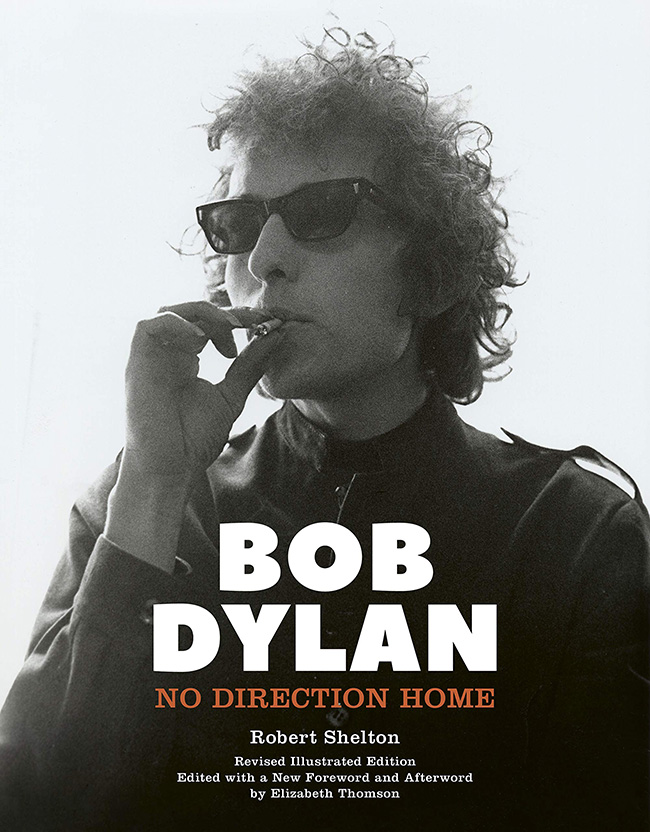

Initially proposed by the author in 1965 and finally released in 1986, an expanded edition followed in 2011 for Dylan’s 70th birthday. An expanded hardback illustrated edition with 150 images “aimed at a younger audience” is released for Bob’s 80th. Shelton’s work was seen as especially sacrosanct because it was one of the first official accounts of “Dylan’s formative years”.

By 1986, Shelton had known Bob for 25 years and was able to offer his own analysis. Despite having close access to Dylan, Shelton confesses the colossal task he set out for himself: “The quest of Bob Dylan is riddled with ironies and contradictions shadowed with seven types of ambiguity”. Shelton invites us through his chronological analysis examining Bob’s life up until 1980.

While there are some aspects of Bob’s family history, Shelton is unable to ascertain that the late Shelton deserves credit for revealing as best as possible: the true Bob Dylan – warts and all. Shelton paints Dylan’s warts with such superb clarity that, in comparison, even the clearest ultra HD images appear opaque. For example, Robert quotes Dave Van Ronk describing Bob as someone who gets “what he can and then discards it”.

Shelton often rebukes his muse calling Bob “the sponge” and “a cruel, self-centred loner…; nonetheless, Robert was also Dylan’s greatest advocate. Sheldon and Dylan first met when Shelton reviewed Bob on 29th September 1961 at Gerde’s Folk City in New York. With both men living in Greenwich Village, they hung out and bonded. Going with his gut instinct in 1963, the author took scorn on the chin when he dubbed Dylan “the singing poet Laurette of young America”. Robert also asserted that Dylan “stamped intelligence on to pop music…”

Bob’s less ordinary musical origins began as an inpatient child and teenager who started and gave up the piano, trumpet and saxophone before settling for the rhythm guitar. In 1955, Bob was part of a trio called the Golden Chords, which split up owing to Bob’s interest in “black RnB”. After being introduced to Leadbelly in 1959, Bob was led “to the roots of the first folk revival of the late fifties!” After reading folk singer Woody Guthrie’s autobiography, Bob became obsessed and mimicked Guthrie’s speech patterns which produced harsher and gravelly vocals.

By opening for the greats such as John Lee Hooker on 11th April 1961, Bob realised he had more to learn about performing and developing songs. Shelton catalogues how Bob tirelessly, enthusiastically and successfully pursued his own personal and musical development, which led to Bob being signed and recording his debut LP by the end of 1961. The following year, Bob was influencing Pete Seeger, and in 1963, “Blowin in the Wind” was released as a single (and at the time was “Warner’s fastest-moving single ever”). Bob performed at Woodstock and appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show.

As Bob got more acclaim (including an endorsement by the Beatles in the Melody Maker in 1965) and going electric, Shelton argues that before Dylan’s “folk-rock” creation, “most musicians including the Beatles had been using insipid, frivolous lyrics”. Shelton seconds his opinions by quoting Maurice Rosenbaum, who reviewed Dylan at the Royal Albert Hall who insisted that “no other” can sing, play guitar or harmonica with “the power, the originality or the fire (of Dylan)…”

Whilst Bob was praised for improving popular music, traditional “folkniks” “rejected” Bob in 1965 when he made the mistake of playing a full set electric at the Newport Folk Festival instead of using a hybrid of acoustic and rock. Ironically, Bob had toyed with four electric recordings for his sophomore LP The Freewheelin Bob Dylan, which didn’t make the cut two years earlier. Shelton recalls how 1966 saw a culmination of events, including Bob being criticised for moving/imitating Mick Jagger at the Dublin Adelphi, Dylan’s song, “Eight Miles High” potentially being banned in the UK as a “drug song” by the then British Home Secretary Roy Jenkins and Bob suffering a near-fatal motorcycle accident. These events took Dylan into a “more tranquil existence” for the next seven-and-a-half years. Despite being in retreat, Shelton recalls how Dylan’s still released albums, including the 1969 Nashville Skyline LP, influenced other rock musicians to pursue country music, including the Flying Burrito Brothers and Captain Hook Medicine Show.

Whilst many (including the extreme example of Alan Jules Weberman) attacked Dylan after 1966 “for his rock star indulges” and “alleged” retreat from left-wing political and civil rights causes; Shelton insists that “In retreat, Dylan refused more money than many pop stars make in a career”. Shelton explains that “Dylan’s message was consistently misunderstood and misapplied”, and Dylan “tried to change his ways”. The summer of 1975 is the best example of this being put into practice when Dylan “forge(d) a community of singers”, which resulted in the Rolling Thunder Revue tour of 1975-76. This tour also saw Bob take up the cause to overturn the guilty verdict of African-American Rubin “Hurricane” Carter and John Artis, who was convicted (overturned in 1985) for committing a triple homicide at the Lafayette Bar and Grill in Paterson, New Jersey. Dylan told Carter’s story on the opening track of his 1976 LP Desire.

When No Direction Home was first released in 1986, Shelton expressed his disappointment when much of the content was removed and sadly did not live to see the expanded version released in 2011. In this illustrated edition (which includes a new foreword and afterword from Elizabeth Thomson, who wrote Joan Baez: The Last Leaf), people across all generations will get to experience the most accurate description of the development of Bob’s musical and poet evolution, his innovative genius and perplexity as witnessed by the author.

Shelton said that Dylan wanted him “to write an honest book”, and Shelton delivered. Bob is frequently recorded as being humble and allowing himself to be vulnerable. The only thing Shelton doesn’t achieve is getting Bob to analyse his own songs and explain the stories and meanings behind them. Shelton offers his own analysis instead. This can easily be forgiven. After all, Shelton spotted Dylan’s potential first and helped to show the world what Bob had to offer and continues to offer. With John Peel later concurring with Shelton on Dylan’s genius, it is impossible to deny Shelton a legacy as an authority on popular music and an emeritus on Bob Dylan.

Purchase ‘No Direction Home (Revised illustrated edition)’ By Robert Shelton

Be the first to comment