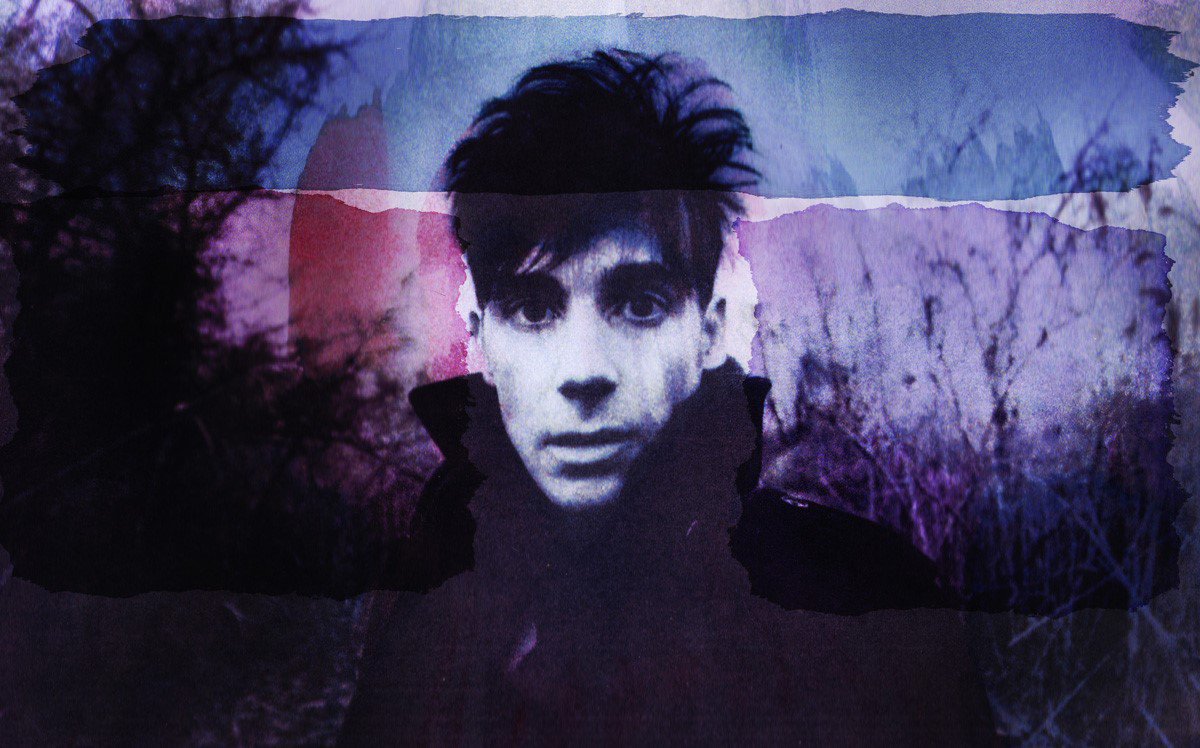

Unpinnable Butterflies, the project of Gabriel Judet-Weinshel, introduces the second single from his upcoming album, Radio Ocean, slated for release on September 24 via sonaBLAST! Records.

Weinshel’s films include 7 Splinters in Time, a filmmaker, photographer, and songwriter, and The Heart is a Hidden Camera, while his music has appeared in In Between Men, Where Hope Grows, and Netflix’s From Baghdad to Brooklyn.

As a photographer, he’s worked with U2, Elvis Costello, Bruce Springsteen, Alicia Keys, Judy Collins, Sheryl Crow, Lil’ Wayne, Ani DiFranco, Lyle Lovett, Counting Crows, James Taylor, The Black Keys, Nicki Minaj, and Elton John.

Produced by Scott Healy of Conan O’Brien’s Basic Cable Band, who produced Weinshel’s previous album, The Exile of Saint Christopher, Radio Ocean blends elements of jazz, classical, electronica, and indie-rock into appealing sonic potions.

A who’s who of talent performs on “Sweet Loretta,” including Gabriel Judet-Weinshel (vocals, acoustic guitar), Kate Tucker (vocals), Scott Healy (Hammond organ, piano), Shawn Pelton (drums), Lee Sklar (bass), Glenn Alexander (guitar), Michael Flannery (guitar, percussion), Mark Luvman Pender (trumpet), Jerry Vivino (tenor sax), Roger Rosenberg (baritone sax), and Richie “La Bamba” Rosenberg (trombone).

“Sweet Loretta” opens on braying horns riding a creamy alt-rock melody reminiscent of early Bruce Springsteen. Weinshel’s voice, slightly drawling, conjures up memories of Tom Petty crossed with Bob Dylan, imbuing the lyrics with tasty timbres. A brilliant sax solo, followed by an oozing organ, gives the tune plush savours.

Intrigued by “Sweet Loretta’s” alluring sound, XS Noize spoke with Gabriel Jude-Weinshel to discover the song’s inspiration, the provenance of the name Upinnable Butterflies, and the distinction between film and music.

What inspired your new single, “Sweet Loretta?”

‘The world is good / we just mixed up the pieces.’ ‘Sweet Loretta’ is a bouillabaisse of imagery, set to a rollicking country two-step, and it features an array of characters. We begin with Adam and Eve listening to ‘the war on the radio,’ practising card tricks,’ and learning to speak. Cut to Godot having a drink at Balthazar (I’m thinking the iconic Soho bistro), remembering the time he tried to bring a god to Joan of Arc but could only find ‘clothes and movie stars.’ The tune ends with Cassandra (Trojan priestess of Greek mythology whose auguries were never believed) and her ‘vision of a red sea’ that makes the people ‘laugh harder and harder.’ In this cacophony of characters, we are importuned to ‘stick around / just another hour ‘till daylight,’ and I think that is the leitmotif of the tune.

The images and characters were mostly dragged up from the old rag and bone shop of my heart. I find there’s a satisfying, mostly unconscious process of words and images announcing themselves when infused with a song (sometimes it happens the other way around, but this time it was the music first). I don’t know who most of these folks or places are (I’ve never been to the Aliosha Bridge), but they seemed at home in the melody and rhythm of ‘Sweet Loretta.’

My hope, I suppose, and perhaps the thematic engine of the tune, is that in this fragmented, often absurdist universe, even at the darkest of hours (and hey, let’s be honest, if you’ve checked the news or just checked the weather, we are there my friends), it’s worth sticking around for fundamental human goodness. I think that’s a Buddhist notion (I’m too much of a mess even to call myself an aspiring Buddhist; maybe I’m an aspiring Buddhist? Isn’t that in itself sort of Buddhist? The idea that folks are fundamentally good. It’s a notion, in these tenebrous times, in which it’s hard to have unwavering faith, but I suppose that’s why I wrote the song.

What’s the story behind the name Unpinnable Butterflies?

I owe the name to my dear friend and frequent collaborator George Nicholas. George is a brilliant cinematographer and director (he DP-ed my feature and featurette ‘7 Splinters in Time’ and ‘The Broken Wings of Elijah Footfalls,’ respectively, and my short The Heart is a ‘Hidden Camera.’) Years ago, one afternoon when I was plagued by self-doubt. We were in a morass of trying to sort through the paucity of options for distributing ‘Elijah Footfalls,’ George buoyed my spirits by saying, ‘Don’t think about the odds of success. Don’t think about failure. We’re like unpinnable butterflies.’ In essence, I suppose, he was saying if you devote yourself to beauty, and maybe to a vision of flight, there is a freedom in that which transcends the world’s typical entanglements.

And then I’ve also always had an Icarus thing (this shows up in my film work a lot—also in my dreams), so another winged creature (whose metamorphosis is also belaboured, at that) seemed apt.

You’re an acclaimed filmmaker. What got you into music?

Thank you—that’s very kind, but alas somewhat inaccurate (the closest to widespread recognition I’ve achieved is when the ‘LA Times’ called my movie ‘a pretentious mess.’)

I’ve always since I was a little kid, been equally drawn to both art forms, and they really feel like twin expressions of the same impulse to make things, or moreover, to find a bridge between what’s inside and what’s outside, to find a foothold in the world that is a little less lonely. (I always think of E.M. Forster, ‘Only connect!’) I come from an artistic family, and my parents were wonderfully supportive of my impulse to create, so instruments abounded in the house. I would just always be doodling at the piano, or the clarinet, and later the guitar. Formal training came way later—not until college, at Sarah Lawrence—because, as a kid, I always eschewed the structure and theory administered by teachers; I just wanted to play, and reading music, much less theory, felt stultifying. But then something shifted, and I was hungry for theory and the tools to play other people’s music and tried to fill in many gaps—classical theory and concurrently jazz theory—as quickly as possible. Scott Healy, who produced both of my singer-songwriter records, was integral to that learning process (my piano teacher in college).

Where music perhaps has a leg up on film is its immediacy. Especially now, with the tools inexpensively and readily available to create professional-sounding work from a home studio, one can make a song, soup-to-nuts, in the course of a few hours, even put it out in the world that very day. And, of course, just picking up an instrument provides even more immediate gratification and catharsis. Though filmmaking also has evolved in its lowered barriers to entry and the speed at which the process can move, it’s still by its nature a more tiered sort of operation: developing an idea and writing a script; finding financing (however modest); pre-production with its tessellation of endless demands; production; post; distribution. ‘7 Splinters in Time’ took nine years from inception to release. About as far as one can get from just picking up a guitar, as in that long arc, what one started out wanting to say inevitably has changed by the time the final work is complete.

Which musicians/singers influenced you the most?

I’m going to make the probably obvious distinction between influence/derivation and the much larger pool of artists who I love or explore (currently in this week’s ‘recently played Spotify queue: Dizzy Ventilators, Matty Charles, James Blake, Beastie Boys, Electric Guest, Dexter Gordon, Jay-Z, Ahmad Jamal, Nicholas Britell, Abdullah Ibrahim, but I wouldn’t necessarily say these are direct influences, as much as I’m digging them all.)

Re influences, I always think of them as my three songwriter Jewish father figures: the tryptic of Leonard Cohen, Paul Simon, and Bob Dylan (probably in that order at the moment, but at various times throughout my life, the order of influence has switched.) When Leonard died, it was like losing a family member.

Which artists, in your opinion, are killing it right now?

Big Thief and Adrianne Lenker; Phoebe Bridgers; Kendrick Lamar; Arvo Pärt, Jacob Collier; Allison Russell; yMusic; Christian Lee Hutson; Dua Lipa; Moses Sumney.

What inspires your writing? Do you draw inspiration from poems, music, TV, or other media?

Since I was in my teens, I’ve always carried a small idea book in my left pocket. I find that keeps a channel open to ideas as I’m moving through the world: images from the street, bits of conversation from a friend or stranger, books to be read, or a passing song lyric drifting up from the unconscious (lyrics I always mark as ‘SL’ in the book.) Alongside song lyrics are movie ideas or images, and sometimes the notetaking for one medium will fertilize ideas for the other.

But otherwise, I try as much as possible to drink in the myriad of art forms: art galleries, films (at this point, maybe we say ‘moving image storytelling’ to embody both film and ‘tv’?—whatever tv is now, as long as we can avoid a word I find anathema: ‘content’), music, books and poetry, theatre and dance (alas, it’s been far too long since I’ve sat in a theatre with live performers.) I lament that I’m a slow (though careful) reader, and I find it also goes against the cultural winds to find time to read now, to read truly, but I determinately am always reading something (most recently ‘Offshore’ by Penelope Fitzgerald, ‘Homeland Elegies’ by Ayad Akhtar, ‘Open City’ by Teju Cole, ‘A Gentleman in Moscow’ by Amor Towles.)

What can you share about your writing process?

I guess it’s worth parsing that my film-writing process, though it intersects, is slightly different from my song-writing process. To go back to the immediacy of music, writing a tune, because so many of the tools of the final creation are manifest and present at the work’s inception—the guitar is in your hands as you are just adumbrating a melody, say—is just more fluid and less tortuous (and torturous) than writing a screenplay.

With a screenplay, it’s just your mind and the feeble tools in that struggle to tell a story: index cards, word documents, idea book scribbles, Final Draft. When I write a song, I often am at the keyboard or guitar, but sometimes recording stems and ideas directly into Pro Tools or singing scratch vocals into a mic. I always think of Picasso’s adage, ‘Ne Cherche pas, trouve,’ which I take to mean dive directly into the process of finding the work, or letting the work find you; something is there, and it’s just about disinterring it. We make nothing in a way; we uncover what is already there. And I suppose, at least for me, there are more tools for digging in the process of making a song than in the process of writing a screenplay.

Screenwriting, for me, is still the most difficult undertaking because you’re just alone with your mind, and I’m plagued by a near immolating self-doubt most days I sit down to it. I’m comforted that, from what I’ve heard and read, far more accomplished screenwriters still feel the same thing. But man, writing a screenplay is just about the most humbling and masochistic activity there is. And yet, I can’t stop.

Follow Unpinnable Butterflies Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | Spotify

Be the first to comment