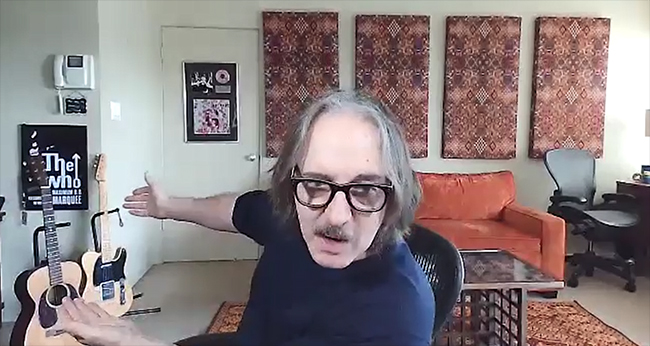

Recently released Divine Accidents by 5 Billion in Diamonds is one of the best releases of 2020. Dan Volohov talks to Butch Vig, co-founder of 5 Billion in Diamonds, the drummer of Garbage, and legendary record-producer about the writing process, music production, working with Nirvana, The Smashing Pumpkins, and more.

How did you approach your work with 5 Billion in Diamonds?

BV: Well, 5 Billion in Diamonds is really a passion project. I’m really good friends with James Grillo and Andy Jenks – the two D.J. producers. The people in the band and all the musicians and singers we asked onboard are amazingly talented or great singers, but they are all super cool people. So, it is very much a labour of love, and the whole process of collaborating with everybody in Divine Accidents was cool.

If you have heard the first record, we wrote the music individually, and then after we wrote a bunch of music, we started reaching out to singers. That was sort of a slow process, and I think we learned a lot making that first record. When we started writing Divine Accidents, we tailor-made each music bed for a specific singer. I think that made it much easier for all our guest-singers to adapt to the new material. So, the record was a lot quicker in terms of recording, and it has a little bit more confidence, a little bit more swagger.

Is it challenging to work on such a record? When you have records like “The Wall,” where a particular concept is put in the core of the record so musically, it reflects the idea. While here, you have just a vibe, a certain feeling you are looking for, alongside different people who bring what they think would fit here and there and something unexpected.

BV: 5 Billion in Diamonds, to me, we are in a different hat. When I am in a band like Garbage, the sensibility we share, and how we approach music differs from 5 Billion in Diamonds. When I am a music producer for, say, The Foo Fighters, Green Day, or whoever, I must remember it is not my music; it is the artists’ music. So, it is a totally different psychological production hat I am wearing.

In 5 Billion in Diamonds, it is very collaborative, and I sort of take a step back as a producer. I do not want to be the one making all the decisions. In fact, probably the most opinionated member of the band is James Grillo; and he is not a musician, but he is extremely passionate about the music he loves. He has a considerable record-collection. So, Andy and I let him in some ways steer where we are going with a song. Andy and I come up with the music when we are writing a song, but we give our guest-artists a lot of leeway in coming up with the parts, writing a melody, and writing lyrics, and I think, they love that! They love being in a band where they can just come in and put their stamp on the music. All the musicians are so great.

Alex Lee does everything on the guitar in one take and is perfect. (laughs) I am not kidding you; he is so good. And our rhythm section – Damon Reece and Sean Cook, who plays with Massive Attack, are brilliant players. We brought Mary Lattimore, a harp-player, in on this record. She plays on a couple of songs, and she is incredible too. So, we work with really cool people, which makes it fun. When we give someone a track, they put their stamp on it, and we are always extremely excited to hear what they are going to do with it.

While studying at The University of Wisconsin, you specialized in film directing. There is a cinematic sound in “Divine Accidents.” It is almost like you approached the writing with a certain mindset. How did you approach your work, and how important is it for you to have this cinematic vision presented?

BV: When I am working in the studio, I see colors in music. There is a term for it called ‘Synesthesia,’ and I get it a lot of times! I close my eyes, and I can get these sorts of unique mosaics of colors all over, or it can be only one sort of solid color. But I also hear music in terms of seeing it in a film or a video. When we started, with the first 5 Billion in Diamonds record, we literally wanted to write some music that we thought could be in a B-Movie like the late 60’s-early ’70s starring Michael Caine – Like a B-spy-movie or a heist-movie.

And at some point, I believe 5 Billion in Diamonds will do a score for a film. I have always tied music and the images together. Whether it is here with 5 Billion in Diamonds or Garbage, we have a screen down in the studio with a movie playing. We can be watching “Blue Velvet,” or we can be watching “The Godfather” or there is this film we have watched a lot called “Incubus” starring William Shatner. It is a bizarre film, but it looks like an Ingmar Bergman-movie. It is black and white with gorgeous cinematography. I find it inspiring to have a visual stimulus in a studio when I am recording. I very much like to tie images with music.

In this project, you do not have strictly defined roles. You used to record drum-parts, guitar-parts, and additional keyboards. How does it feel for you in this collaborative model when you have no idea what to expect?

BV: We really try to play on everyone’s strengths in the band. And when we start a song, James Grillo will play these obscure records to reference textures and reference a groove or the arrangements, and Andy and I will try to flesh out the initial music like that. I play some drums on the record, but Damon played a lot of drums. I also play Bass, play the guitar, and a lot of keyboards. I have got a Moog synthesizer over here that I like to play. I like to do this, which goes back to my film-school days and electronic music at the University of Wisconsin. I like to add these little spacy textures and things in the background that can be floating around.

Andy Jenks does that too. He is a brilliant keyboard player, and he likes to layer all these subtle textures that you could bring in and out of the mix and give it a psychedelic, almost surreal quality. Some of the songs are more straight-ahead, like “Into Your Symphony,” which is very much more of an 80’s reference. That song has an almost Cure or New Order feel to it but still has many textures. If you put headphones on, you will hear many things that we like to bring into all the songs.

How different is your approach when you are working as a collaborator, rather than being a producer or musician\co-writer?

BV: Well, I like to take a seat back; it is a different mindset. I mentioned this earlier it is like wearing a different chef’s hat, and I can just decide: “I want to work on a keyboard-part!” or I can decide: “What wine shall we open today?” (laughs). Somedays in the studio with 5 Billion in Diamonds, my most significant decision was what wine we should open? Days like that could be very fruitful.

Being a drummer and dealing with rhythm structure as one of the only constants, you always should think about what the songs need. Whether these are songs like “Only Happy When It Rains” or “Empty,”– what helps you building this architecture of a song-structure and defines your musical accents?

BV: That is a tough question. When you are working on a song, a couple of elements come into play that will define that song. If there is a singer for one, you want to make sure that the singer sounds good and that they are front and centre, and the tone of the voice is right, and you are getting some emotional impact from it. There is a feel of the track from the rhythm section or whatever you have got, and there are arrangements; all other things go into it. Whether these are guitars, keyboards, or strings – It is a balancing act. At the end of the day, you must be objective and step away from it and pinpoint the most important things because it is easy to get lost in a song. It has happened many times in Garbage because we are very guilty of recording a lot of tracks.

Between the four of us in Garbage, we have a lot of different ideas, and sometimes, when it gets to mixing, you must go through it and decide what you are going to get rid of. So mixing is taking things out of a track, which happened a lot in 5 Billion in Diamonds. Some of the songs have many keyboards—a lot of cool ambient tracks and sequencers. If you put them all in – they got too busy! The song would start getting too dense. I mixed the record in my studio, so I had to start taking things out and strip the songs back a little bit.

Once I got it stripped back, where I thought the arrangement was lean and efficient and worked very well – then James Grillo would start having me add little things back in. He would say, “Add that little sequencer, add that little drop in the bridge.” So that is cool! And I think it’s a good way in 5 Billion in Diamonds to work. We throw a lot of music into a song; it’s like a painted canvas. We record many different parts and textures and then pull it all back, and we will work on the painting until it all becomes beautiful. I love that process. It is fascinating because I never know where a song is going to go when you start. Especially when you get to mixing – you can make so many decisions. You can profoundly change how a song sounds by what you leave in the mix or what you take out.

Keith Moon and The Who are one of your first sources of inspiration. Keith is more of a jazz-drummer in the sense of somebody being unexpected and provocative. While your drumming technique is slightly different – what has been moving you as a drummer, and what helped you master your style?

BV: Well, Keith Moon was what got me into playing the drums. I saw them playing a T.V. show, and I was just blown away by how dynamic he was and flamboyant and kind of out of control, and I begged my parents to buy me a drum-kit for Christmas. They bought me a cheap 50-dollar drum-kit, and I started playing every day. I realized, very quickly, I could not play like Keith Moon (laughs). I just realized: “I can’t do that! What can I do?” So, I started listening to Beatles’ records and Rolling Stones records, and I realized I could play more like Ringo Starr and Charlie Watts. So, I have always modeled my drumming on being a straight-forward, simple rock-drummer.

Even in Garbage, I do not really play too many flamboyant drum-parts or drum-fills. I sort of look at the drums as the backbone of a track, and they should be there just to support the music. Now and then, I will throw in a cool drum-fill or some pattern that pushes the bar a little bit. But I try to make sure that the drums, whether it is something I am producing or with the band that I am in, fit into the song’s context.

Can you remember the moment when you decided to become a producer?

BV: You know, I fell into being a producer just from working with bands. When Steve Marker from Garbage and I started Smart Studios in 1984, there were many cool local bands in the Madison-music scene. So, we got a lot of work right away, coming to our studio. I played in a band at that time called Spooner, and we had been making our own singles and E.P.’s. I was interested in recording because I came from more of a pop-sensibility, which I really learned from my mother.

I tried to bring any hooks I could hear in the bands’ I was working with, even if these were bands like Killdozer or Tar Babies. If I could hear a hook, and I thought it could be focused better, I would say, “Maybe you should tighten it up or don’t play that riff at the end play it a little tighter here and let the drum-fill play and then come back to the beat.” – they are like, “Ok, we got it!”. And so, I was just throwing out opinions, and I did not realize at that time that is what the producer does. A producer is really someone with the idea that an artist can trust. I remember in late 84 or 85 when someone said to me, “You’re the producer! We are going to give you a production credit on the record!” and I’m like, “Ok! I guess I am producing this.” So, I never really made a conscious decision to say, “I’m going to be a record-producer!” – I just started making records and engineering. Because I was opinionated, I became a producer.

What were the people you were looking for? Not much of producers but sort of mentors, per-se.

BV: When I started, the great thing about Smart Studios was I did not really know what I was doing, and neither did the bands. Many of them had never been in a studio before, so many of them were freaked out the first time we would do a playback. I could mic everything up, and I could do a take, and they would come into the control room and listen and say, “Holy shit! We sound like that. That’s so crazy!”

Because they were used to playing in a basement with an amp and a cymbal pounding away in the corner of the room. So, I was able to experiment a lot, and I got many artists I work with to do the same. Again, they did not know, and I did not know. I sort of had to do that to a certain extent because the early studio was limited in terms of our gear – It was not a state-of-the-art studio. It took us a long time to build up, get the 24-track, and get some decent microphones and stuff.

I always was looking for a way to make things sound exciting, and luckily the bands I was working with were really into that too. These days, many engineers and producers can go to schools; there are all these great recording schools out there. You can learn how to program, use Pro-Tools, and learn how to write orchestrations, but I had to learn by the seat of my pants. I never had these schools. I just had to figure it out on my own, which served me well. It did force me to experiment and try many things, and there was a lot of air in that! For every great recording I did, there were a lot of recordings that sounded horrible! But when you record something that sounds horrible – you learn from that quickly. Why did that sound horrible? Do not do that again (laughter)!

When you started Garbage, there are lots of contradictory things about that first record. Especially this transition between analogue and digital recording. What was your work methodology while recording that first Garbage record?

BV: Well, the debut Garbage-record to me sounds like an anomaly – It is bizarre. We used samplers on that record – this was before Pro-Tools. But we were recording music onto a 24-track and then transferring it on a couple of different samplers we had. We were either looping it or manipulating, filtering, or adding distortion to it, and then we would sync it up and print it back to the reel. Some of Shirley’s vocals were run from the reel into the sampler and back into reel-to-reel tapes so, it has this weird sound to it! And part of it was just transferring the music back and forth.

Also, I had done so many rock-records at that time – I was bored with that approach: guitar-bass-drums. And using the samplers, we brought in a lot of sound processing and drum-loops and brought in electronica and hip-hop beats. We mixed all those amongst fuzzy guitars and pop-melodies, so, I think, the first Garbage record sounded strange. But the songs were hooky enough, so we stuck out at that time. That first record did not sound like anything else on rock-radio at that time. I think that really helped us.

Over the years of your career, you have passed through different stages – stylistically, first. In the early 2000’s – after “Bleed Like Me” was recorded, you went on hiatus, and you got back to producing bands. Was it a difficult transition for you? After years of touring, recording albums with your band members.

BV: When Garbage took off, none of us had any idea we were going to get sucked into a 10-year run. We did four records and four long tours, and that is really all I did at that time – I just focused on Garbage. I did mention a few remixes, and I did a couple of radio-mixes for a couple of artists, but I did not really do any album producing – because I did not have the time. When we took that hiatus after Bleed Like Me, we needed it; we were all really burned out in the band. I think the music climate had changed from when our first record came out. We felt we were swimming away out of a sea, away from any friendly confines, and we just knew we needed to go away and clear our heads, and everybody reclaimed their lives. I thought it would be about a year, and it turned into almost seven years! That is how much time we needed off.

But I have to say that it really helped the band immensely because of that time off. We just finished mixing a new Garbage record coming out in May or June, and I think it sounds great! The band’s getting along great! We are all very connected in the music we are making were trying to push ourselves in terms of how we are writing and the arrangements we are doing. We have been together for almost 25 years; I think If we had not taken that break, we would not still be here after Bleed Like Me. So, it was useful first to clear our heads and refocus. I am glad we did because, as I said – I am excited about the new Garbage record.

Is there is a movie you can compare this new Garbage-record to?

BV: The new record is quite eclectic and schizophrenic with some beautiful songs and some that are edgy. There are a couple of songs with heavy guitars that sound like traditional Garbage. It is hard for me to describe – There are a couple of songs that sound like Roxy Music. There is a song sort that references Talking Heads. And the best thing is that Shirley’s lyrics…She wrote most of them in 2019, but her lyrics are very much about 2020 and about how crazy and fucked up the world is. Every song is touching a subject of the swirling madness that is going on around us.

It is like she saw 2020 coming last year when she was writing these songs. So, I wish we could put the record out right now! It is perfect timing for it! But because of COVID-19, it is not coming out before…probably May or June 2021. I do not know what film it would be! You will have to wait until you hear the record, and you call me back and tell me, ok?

When Steve and you founded Smart Studios, you were mostly recording different local punk-rock or kind of punk-rock artists. At that point, you had primarily been focusing on engineering work. What defined your working ethic and approach you had to work in Smart Studios?

BV: I always wanted to make records that sounded big and widescreen. When Smart Studios first started, as I said, we were so limited with our gear. And our first recording sounded lo-fi and scrappy, but there is a charm in that. I kept learning! Every record I did – I learned more about recording drums, I learned more about making a guitar-sound better, mixing them better, and recording a vocal better. It did not happen overnight; it was a slow build. Die Kreuzen could have been Jane’s Addiction! They talked to a couple of major labels, and I got a call from one of the labels about producing them, and then something happened, so the deal did not happen.

I know they were bummed about that because they were right on the verge of breaking into the national scene – They were a fantastic band! I always wanted to make records that were clear and focused, like Die Kreuzen or L7. Even records I make now or made recently like Against Me! Or Green Day or Foo Fighters. I want there to be energy, but I want it to be focused. I want to hear the tones in the guitars and feel the drum – Not just the energy but being able to listen to the snare drum and different parts and the sound of a kit.

I have always been that way! I keep saying this, but I wanted to make records that sound focused. Just being clear and focused. When we made Siamese Dream with Billy Corgan, that was also something of a ground-breaking record because Billy and I set the bar high. We wanted the guitars to have a specific tone and a lot of those tracks to sound symphonic with basic guitars, Bass, and drums. There are a few keyboards on the record. That was before Pro-Tools! You had to play everything, and I had to make sure it was recorded right on the tape. We worked pretty much every day for five months on that record. Then we went to L.A. with Alan Moulder and mixed every day for 6 weeks. So, it was a long, arduous record, but I think it still sounds rather good. When I say clear and focused and really wide-screen – I think that album really defines it. I believe Siamese Dream is really that kind of album.

In one of the interviews you did over the years, you said that the secret Nevermind has despite Kurt Cobian’s lyrics and writing being so incredible that it sounds like a live record. What helped you to capture that level of energy the band had reached at that point?

BV: Listening to Nevermind – the most significant difference between when they came to Smart Studios to do the Smart sessions and going into Sound City Studios was – Dave Grohl had joined the band. And I did not know at that time that they had practiced every day for six months. So, they were tight. I used a click-track on “Lithium” on the record, but that was it because Dave is rock-solid on drums and played so intensely that he really forced Kurt and Krist to play tight with him, and they did! They really locked in as a band so, I did some editing in the studio.

But for the most part, once we had all sounds right, I would just go for the right take each day. And they usually got a keeper-take in two or three, sometimes four takes it was not longer than that. Kurt did not have the patience to do any more takes anyway. The record, at that time, got a long of negative feedback. People were saying it is too produced, it is overproduced – and that is just laughable.

Because it is like – 8 tracks of drums, Bass, one of two guitars, and Kurt sometimes doubling his voice, either he would add in harmony or Dave would sing in harmony. Of the 24-tracks, maybe I used 13 or 14 tracks. Maybe 15 on some songs, but It was dead simple! I think that is one reason why the record has stood the test of time – It does not sound gimmicky. Some records have a sonic stamp on them where you can say, “Oh, it’s 1987 because of that keyboard sound” or “That’s the early 80’s. I can tell it by the giant snare-drum sound!”. I think the production makes Nevermind sound timeless – to a certain extent because it is just bass-drums-guitar and a singer.

Being in punk-bands in the ’80s and going through all the years of your career, you have always been very much of a DIY-guy in the sense of somebody doing his own thing without any involvement besides. Being a fan of producers like Chris Thomas, you brought this very characteristic feel to all the recordings you have been doing. Nevermind sounds like punk-rock, as does Siamese Dream. What did you learn from punk-rock, and how have you transferred this very characteristic feel into what you are doing as a producer?

BV: Well, the sound does not have to be pristine and beautiful to be interesting. I think I learned a lot of it at film-school with electronic music at The University of Wisconsin – Like noise can be beautiful. In “Stupid Girl,” there is this noise that comes in the B verse before it goes to a chorus. It is a loud glitch that came out of one of the samplers. And I was like: “That’s a hook! Let us put that in there!” – I think, Duke and Steve were like: “What ?” – and it goes like: “Phhh! Kkkrhh! Whhh!” – It’s quite loud in a song, and yet every time I hear it, I think: “That’s a hook!”.

I think one of the things I took from punk-rock was that noise and mistakes could be hooks. Like I said – you do not have to make a Steely-Dan-sounding record to capture people’s attention. Sometimes accidents can become a motif in a song, or that is what you remember from a song. It is important to remember that human beings play music and want to make sure that you keep that human element in there.

Sometimes that can be a little messy, a little noisy. It could be a mistake. The important thing is you must know when that is. A producer has to go: “That’s good! Let us keep it!” or “No! That is bad! let’s get rid of that!”. And that happens every day in the studio. Every day, I walk into the studio, I think: “Something’s going to happen with the song we work on!”. Inevitably it always goes somewhere else, and that is what I love about being in a recording studio! Because the journey is unpredictable. And I look forward to that – every day!

Listen to ‘Divine Accidents’ – BELOW:

Great article mark